Great Arkham is a thief. One day you get out of bed, and you’re in a city you’ve never seen yet know intimately. You have a job, a favourite pub. You go about your day, and there’s something nagging at you, but you can’t place it, so you do your best to put it out of your mind. Most people live their entire lives in Arkham in this state of unease. What were you doing before coming here? Why did you come here? How did you come here? Isn’t there a life waiting for you outside?

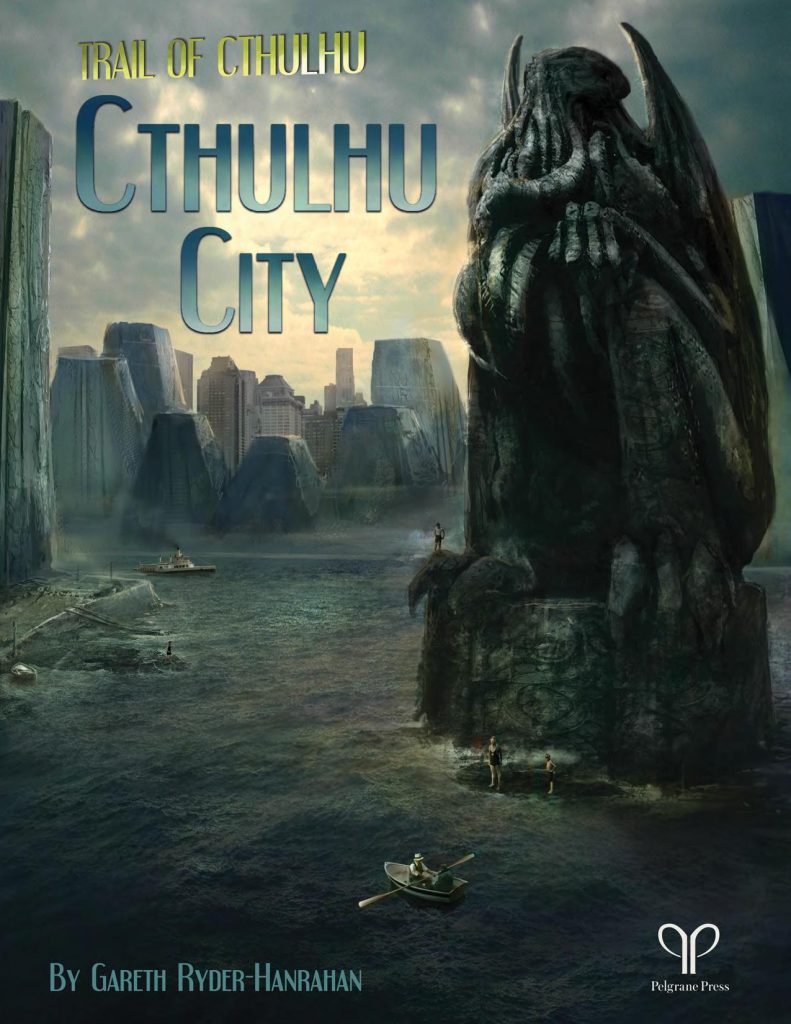

This isn’t quite a review of Cthulhu City the campaign book written by Gareth Ryder-Hanrahan and published by Pelgrane Press, though I’ll be gushing about it. Neither is this a review of Trail of Cthulhu, for which this campaign book is written, though it did its job remarkably well. Rather, this is an eulogy for a campaign that was meant to last a few months and instead grew in the telling to well over a year, drawing in other campaigns I’ve run and, no doubt, spilling into ones I’m yet to run. Just like Great Arkham, the “Cthulhu City” itself, it spread. There’ll be some spoilers, naturally.

Great Arkham is a prison. Take a train, it will be stopped by the Transport Police. Typhoid quarantine, they say. Take a bus, it’ll blow a tyre. Take a boat, waves will threaten to overturn it. Go into the woods, you’ll wander for days before coming back to Great Arkham.

Let’s start with a confession: I’ve barely read any of H.P. Lovecraft’s works. I’ve read about them, seen them implemented in games, but every game of lovecraftian horror I run is a tribute to a tribute. This hasn’t stopped me: I’ve previously run a series of very loosely connected brief campaigns of tremulus, which I named in my self-indulgent manner “The Nyarlathotep Trilogy”. Most of my players haven’t read Lovecraft, either. This was the first hurdle: Cthulhu City is a love letter to the mythos universe. Its most basic premise is “what if all of these stories and characters weren’t just in a shared universe, but in the same city?” Dunwich, Innsmouth, Kingsport – these are all districts of Great Arkham. Colour out of space and re-animators, Charles Dexter Ward and professor Armitage, they’re all here. But I barely recognize these people and monstrosities, they’d mean nothing to my players. The solution was obvious: just like Arkham had somehow absorbed all its source material, it had absorbed the characters from our previous horror campaigns, PC and NPC alike, living and dead. Only one of my players had an “oh shit” moment when they heard the name Charles Ward, but they sure all had one when they recognized the impossibly alive professor Mastodon Jones, followed by an “ohh shiiiiiit” moment when they linked William Robinson the owner of Chemical Works processing plants with Will the one-armed teenage veteran of the Great War and a priest of Nyarlathotep, the villain of the game in which Mastodon Jones was a PC.

Great Arkham is a time-space aberration. It is impossible. It doesn’t make sense. It has drawn not just people but entire places from different time periods into itself, and trapped them all in its maddeningly vague history.

Cthulhu City is an unusual setting book. It has strong themes, but leaves putting details together to the GM. It asks questions and offers suggestions for what the answers might be. What is Great Arkham, why does it exist, what do the black monoliths dominating its skies do? Up to you. Each NPC write up, and there are a lot, from named individuals to stock characters, offers three variants: Victim, Sinister, and Stalwart. Each location description comes with Masked and Unmasked options. Each district description starts with several brief scenes that might happen there. Everyone’s hiding something. Every place has a horrible secret. These are all bits of story one can plug into their game. They wouldn’t all fit into a single campaign, or a single city for that matter, but that works for Arkham. There is no canonical Great Arkham, they’re all real, as real as Arkham gets. In practice I rarely used these stories, beyond the key NPCs and locations, but I still greatly appreciated them. Not only were they fun to read, they offered examples of what could be, sketched out the space in which I could imagine my own weirdness.

Great Arkhaim is the embodiment of the American Dream. The city is rife with opportunities, all you gotta do is have your eyes and your mind open to spot them. All truly succesful men are geniuses, and all geniuses are mad. Embrace your madness and prosper.

While the city is drowning in mythos, the games set in it are still fundamentally about people. Many of the plotlines suggested in the book center on the people who were exposed to some aspect of the impossible and immediately tried to use their newfound knowledge to turn a profit, or otherwise benefit themselves. In other lovecraftian settings, mythos is often the end goal: mad cultists are summoning a vile god to end humanity, or a monstrosity is rampaging unimpeded. There’re plenty of mad cultists and monstrosities in Arkham, of course, but by and large the city is made up of regular folk who, while vaguelly aware of the wrongness of it all, go about their regular lives. To them, mythos is the means to their mundane goals. This was a refreshing shift in perspective, providing the “villains” with motivations other than “mad and wants to end the world”. Perhaps one had to drown the setting in mythos to allow for human elements to rise to the top.

Great Arkham is the best city in the world. It has its warts, sure, but what place doesn’t. Keep your head down, work hard, and you will have a decent life, what else could anyone ask for. And even if you do everything right and things still go wrong for you, well, life ain’t fair, is it. Not like the city’s to blame for your misfortune. Is it? Besides, where would you go, some big city where no one knows you? No, there’s no way I’d leave Arkham.

In an investigative campaign, it’s very important to track who knows what. In Ctulhu City, where no one knows the truth but everyone has their own perspective, that gets especially tricky. I decided early on to summarise this by having each significant NPC discuss the nature of the city with the PCs the first chance they get. This helped me keep in mind not just their knowledge, but their attitude as well, and demonstrate it to the players. The snippets interspersed through this text are such musings.

Perhaps even more importantly, the players needed to keep track of what they already knew. At my insistence, they started a session log, which, just like the campaign it documented, grew to monstrous proportions: in the end it stands at 135 pages. I also wanted to both demonstrate that the city didn’t revolve around the PCs and show how it reacted to their actions, as well as sow the seeds for potential future investigations. Arkham Advertiser was the answer to all of these: a newspaper front page I’d produce whenever felt right – you can find an example below. It also was fun to write, especially the ads. Next time I produce such newspapers, I would propably reduce the actual articles to only a couple of paragraphs of key information. And maybe put the saved effort into layout and proofreading.

Great Arkham is a city occupied. All of us close our eyes to this simple truth. We pretend everything is alright even as we sacrifice ourselves in service to its inhuman captor. We bear the chains willingly, because to question the nature of our unnatural society is to become an outcast. None of us are strong enough to resist this oppression on our own. We must rise up together and overthrow the ancient evil that is capitalism.

Another technique I used was inserting snippets of daily life in a city occupied by mythos into the game. Small scenes of weird menace that don’t lead anywhere. It worked great, in the sense that players immediately would latch on to them and spend entire sessions chasing down clues as fast as I could improvise them. They saw a teenager being chased by transport police toss his bag over the fence before he was grabbed. Not only did they recover the bag to find a map of Massachusetts where Arkham is a small town and Dunwhich is a separate village hundreds of miles away, they broke into the Arkham Sanitarium to save the kid. The kid, Alex, was looking for his sister, Carmen. And so it went.

Another time, a PC heard faint voices coming from her shower head, followed by the stench of rotting meat and finally maggots pouring out. Creepy but ultimately meaningless. Of course the PC looked for the meaning. This lead to people infested and possessed by maggots digging new groves in their brains, to metamorphosis, to a mothman trying to make more mothpeople. Along the way there was a high school football team called Mighty Mothmen, complete with a mascot, and a bit of emergency magic surgery involving an eye and a key after a PC donned said mascot costume and couldn’t take it off. Also Native American rock art depicting something very much like a mothman god found in the caves in Dunwhich woods. The mystery kept revealing new layers.

Great Arkham is wasted potential, just waiting for someone with a vision. It is in a unique position, sprawled across histories: there are many timelines, but only one Great Arkham. With it as our beachhead, we could make history itself bow before the Yellow King.

Turned out, the mothman behind it all was a mothwoman calling herself Camilla, and all the infested people were gathering for a performance at a graveyard. Which either tells you nothing, or makes you go “oh shit” yet again. I want to run Yellow King RPG some day, also by Pelgrane Press, and this seemed like a natural tie-in, Carcosa’s attempt to take over Arkham. Naturally, PCs got into the performance and became art students in end-of-19th-century Paris, the setting of the first part of YKRPG. They attended a masked graduation ceremony lead by Camilla, followed by a sea voyage to Great Arkham to spread the word of the Yellow King via art. While on board, PCs took part in writing the King in Yellow play (which they were already performing or possibly living), adding antagonists to the plot, and, with minimal prodding, styled these antagonists after themselves. So when they disembarked into the graveyard and the play was over, they were the characters they wrote, still opposing Carcosa. Were they investigators dreaming they were moths, or moths dreaming they were investigators?

To tie all this together, I had Alex reveal the “real world” he comes from, the one outside Great Arkham, was not the United States they assumed, but the United Empire of America ruled by Emperor Castaigne. That is to say, the world of Yellow King RPG. Up until then, the PCs thought they’d escape Great Arkham, now they weren’t sure there was anywhere worth escaping. To make matters worse, Alex and Carmen, on their way into Arkham, bought wormy peaches from a roadside salesman. Alex bit into one and spat it out, while his sister was hungry and ate a whole bunch. Did I say wormy? I meant maggoty. PCs immediately and correctly realized Carmen was the patient zero of the maggot-mothman infestation, making her the mothwoman Camilla they had just killed and buried with the help of Alex. Which would of course come back to bite them.

I describe all this is not just because I’m damn proud of the plot we ended up with, but because it grew from throw-away scenes into a monumental story arc that tied mothmen to Carcosa and its convoluted plot to invade Great Arkham by violating quarantine restrictions on fruit import, and that’s without even mentioning the pre-Arkham village of Nuveau Carcasson, a.k.a. New Carcosa, a.k.a. Newcastle district which has always been in Great Arkham after this story arc was resolved – can’t invade a city if you’re a part of it. Aaand I’m rambling again. In retrospect it is amusing I’ve felt the need to invent a whole new faction vying for control of Arkham in a setting already full of them, but this freedom to add to a setting is integral for it to be not just a fun read, but actually fun to use in a game.

Do you think people of the Dreamlands have their own Dreamlands? They dream, after all, just like we do. And if they do, do you think our reality is the Dreamlands to someone else? That would explain a lot about Great Arkham.

Once we’ve dragged past and potential future campaigns into the current campaign, it was hard to stop. We have a long-running Shadow of the Demon Lord back-up game, which we discovered was actually in the Dreamlands – one of the PCs picked up the Dreaming skill and ended up in the middle of a SotDL adventure. As a side note, this meant the Demon Lord is Nyarlathothep, a fact that changed nothing yet amused me greatly. When we inadvertently opened a portal to Unknown Kaddath underneath the Arkham city hall, I looked at my bookshelf and pulled out Ultraviolet Grasslands and the Black City, a psychodelic heavy metal road trip game. Given that my understanding of Kaddath is limited to “weirder Dreamlands”, it was a great fit. Both even have mind-controlling cats!

Coup de grâce, however, came when I managed to tie Arkham Horror the board game into the campaign. As we delved deeper into the mystery of the nature of Great Arkham, this became a major piece of the puzzle, another perspective to which the PCs gained access. Locations on the board game map, we determined, were the black monoliths dominating the skyline of Arkham. PCs could enter through any of them and have a friendly chat with the entity they dubbed “the Gatekeeper” before exiting through any other monolith. All they had to do was draw a card corresponding to their new location and deal with whatever it said. This was an interesting improv exercise, translating board game cards with their wacky single paragraph events into a roleplaying environment. Some of them just say “a terrible monster appears,” and I did reserve the right to draw another event if the first one just didn’t work. Overall, they worked great as prompts, leading to some cool scenes we would never have had otherwise, including a spontaneous trip to the founding of Great Arkham.

Great Arkham is a dam. For centuries, it has stood betwen the mythos and the mundane. And just like any dam, it has a power all its own. Some would drain it, deny the divine, reduce Great Arkham to another forgettable city, perhaps to nothing. Others would open the floodgates and let the mythos through. Then there are those who quite like the way things are. Those who can draw upon this accumulated power.

The book suggests the following campaign concept: you start with street-level, individual mysteries, move on to investigating cults and other powers that run the city, then finally confront one or more of the big mysteries of the city itself. The Ritual of Opening/Closing is a convenient plot device that forces confrontation and ties the latter parts of the campaign together. Half of the various factions in Arkham would love to, given the opportunity, perform this incredibly dangerous ritual, ending the city and possibly the world one way or another. This works, but was the only part of the book that was a bit generic for my tastes. As the campaign progressed and factions and their motivations became more defined, their versions of the ritual and what it would achieve shifted. I still used the tried and true threat of cultists-ritual-apocalypse, but the individual apocalypses varied significantly. Church of Conciliator still wanted to invite Azathoth to Earth, with immediate and obvious consequences, but Yellow King wanted to use Arkham as a beachhead in reality conquest, and Necromantic Cabal wanted to incarnate a “human” god.

Arkham is an oppressive setting with a tangled web of conspiracies and otherworldly forces, it is inescapable and overwhelming. Scratch the surface of any mystery and you’ll find two more underneath, vanquish a cult and you’ll free up their opponents to advance their schemes. I tried to convey this by drowning my players in clues to pursue. At any time there’d be not just multiple avenues of research, but multiple distinct investigations they’d have to deal with, in addition to the aforementioned daily life occurrences. This combined well with time pressure as the central campaign structure: the PCs knew the time window in which the ritual was possible was rapidly approaching, even if they didn’t initially know when exactly it would happen, and we tracked every day in a 1937 calendar. For every subplot, I figured out the likely timeline of its development if the PCs did nothing, then put key dates into the shared calendar, coded after Mythos deities. The players didn’t know what “Byatis” stood for, but they knew it was coming.

As the result, the PCs ran themselves ragged, trying to battle a city’s worth of mystery and horror all by themselves. They were forced to triage. A friend left a cryptic message and hadn’t been seen since? Better hope he’s alright, the party’s putting out bigger fires. He wasn’t. Trail of Cthulhu/GUMSHOE, the system for which Cthulhu City was written, worked wonderfully here. In it, characters spend points they’ve assinged to skills to improve their rolls or get bonus effects. Some of these points replenish with a good night’s rest, but most only do between investigations. Critically, Stability (which helps one to not go insane, a useful skill in a lovecraftian horror game) only refreshed when spending quality time with loved ones. Which meant carving out crucial time to do so and making sure there were un-broken loved ones left who they could still face. This list grew quite slim by the end of the campaign.

I have to commend ToC for forcing us to come up with the list of NPCs that PCs rely on. Cthulhu City goes further and mandates we also list ‘entanglements’, who rely on PCs. This excercise was somewhat overwhelming during character creation, and would perhaps be better stretched out through the first investigation, but by the end of the campaign all these characters were involved and suffering for it. Likewise, multiple Pillars of Sanity were shattered and one PC even talked his way into destroying his own Drive, so all the prep was worth it in the end.

A direct consequence of the time pressure approach was how desperate the players were to use every hour of every day at their disposal. That’s largely the reason the campaign went on for so long: as we approached the ritual week, we went from covering a couple of days in a session to a day, to half a day. And the more attention to detail we paid, the more space I had to introduce more horrible twists. We nearly Zeno’s paradoxed the campaign into infinity.

Great Arkham is a mirage. A lie. A dream. It’s not real, is my point. Nothing here is real. No one. It is not real because it can’t be real. The things I’ve seen, the things I’ve done. I don’t feel guilty. Why should I? Nothing we do here matters.

Just like (our version of) Arkham spreads through worlds and histories, so did the real world reach into it. We began the campaign near the end of 2019. In it, a fake pandemic is used to control the populace, authorities commit ritual sacrifices, newspapers lie to keep everyone docile, and masks are a major signifier of one’s allegiance to a sinister force. As 2020 went on, this fun romp through conspiracy theories became decidedly weird and at times even uncomfortable. The heroic investigators opposing these conspiracies sounded like real life raving lunatics in the daily news (and fortunately not many of our close relatives or friends). Even gaming gets complicated when living in interesting times.

Near the end I was worried it got to be too much. Too oppressive, too gruelling, too close to home. My players assured me they were fine. Having the backup game with much lower stakes, dark fantasy with constant threat of PC death though it may be, certainly helped. However, we all agreed we wanted to do something much more lighthearted afterwards. Still, at the end of the campaign Great Arkham remains. Which means it will undoubtedly spread into future campaigns we play. There’s now a permanent portal and a small Arkham outpost in the Ultraviolet Grasslands – we’ll pay them a visit when we get around to UVG. Shadow of the Demon Lord campaign is in the Dreamlands, so an arkhamite cameo is always possible. Yellow King RPG is already tied in. Maybe we’ll do Fate of Cthulhu with its time-travel shenanigans and actually “solve” Great Arkham. One thing is certain: all I need to do to terrorize my players is mention Arkham’s black monoliths appearing on the horizon.

Clearly such mad sprawling sandbox campaign is not the only way you could enjoy Cthulhu City. You don’t need to drag past and future campaigns into it, you don’t have to write fictional newspapers, or pull out the board game. But… you could.

Great Arkham is the answer to your prayers. Ever since you’ve learned of it, you sought more: books, movies, art, games, anything to sate your growing longing. It was just a game, merely a fantasy. A mythos. You called for it, with every unpronounceable name you learned you called for it, with every maddening detail you so eagerly absorbed you weakened your ties to what is, with every frightening daydream you reached out to what shouldn’t be. And it heard you. I heard you. You are home now, and you will never leave me. Welcome to Great Arkham.

Wow. That’s a brilliant approach. I would love to see that campaign log and the gming notes.

My notes wouldn’t be comprehensible to anyone including myself, I’m afraid. As for the campaign log, here it is. It eventually becomes a blow-by-blow account of every session, and thus a bit easier to follow. Names get mixed up, a PC disappears because the player leaves, and overall it’s a giant mess. Enjoy!