In the last few years, seemingly any time favorite RPG campaigns are brought up, someone mentions Impossible Landscapes. It’s a huge campaign book for Delta Green written by Dennis Detwiller, “of wonder, horror and conspiracy”, “a pursuit of the terrors of Carcosa and the King in Yellow”. I’ve just finished running it, and boy do I have opinions. I’ll spoil the entire thing, only read this if you’re definitely not going to play the campaign but are considering running it.

The story

First, an overview of the campaign itself. It consists of 4 major chapters and several “side” locations that could be visited at various points of the game. It all starts in 1995 with Night Floors, previously published as a stand-alone adventure. Abigail Wright is missing, and agents are called in to investigate a possible occult connection. Turns out, Abigail got her hands on a copy of the poisonous play, the King in Yellow, and passed it around the Macallister building she resided in, “infecting” everyone there and ultimately connecting the building to Carcosa.

The “Night Floors” are what’s nowadays called a liminal space, impossible extra floors of a 4-storey building, full of strange rooms, branching repeating passages, and people coming out of nowhere and disappearing in empty rooms. The agents stumble into these Night Floors and wander around experiencing the many inventive creepy scenes they have to offer, until they find their way back to reality. They do not find Abigail – she’s gone further than they could. The assignment ends in failure, all the agents can do is decide what to do with other residents of the Macallister building as well as the building itself.

20 years later, when the strangeness of Carcosa is safely out of their minds, the surviving agents are called on another mission: some friendlies committed to a mental hospital are missing. Thus begins A Volume of Secret Faces, the most sandbox-like part of the campaign. It’s a tough one to prepare for, as there’re so many things for the agents to investigate, so many threads to pull on. The friendlies never existed. The curator for this mission is compromised. Should they find out about this unsanctioned mission, Delta Green may try to eliminate the agents. The mental hospital is touched by the madness of the King in Yellow, and all of its staff have their own strangeness going on. Also, demons. It’s a lot.

Sooner or later, the agents spend the night in the hospital, getting drawn into the Night World yet again: they find themselves in a nightmarish reflection of the mental hospital, where they are the patients. The only way out is to trust a strangely helpful demon, attend a dance performance, and escape a murderous clown by drinking red goop called patzu. When in Carcosa, do as carcosans do.

Third chapter, Like a Map Made of Skin, is basically a chance to “clear” some of the locations from the previous chapter. The agents are back in the real world, only to find it’s no longer all that real. They’re hunted by the authorities, as well as spectres of an old Delta Green clean-up crew, STATIC. They’ve received an invitation from Abigail asking them to come to a hotel that definitely doesn’t exist, and may never have existed. Once the final pursuit of STATIC begins, they’ll end up there anyway.

Part four, The End of the World of the End, is the shortest and is mostly an adventure rather than an investigation. The agents find the way to the labyrinth underneath the hotel, find the spirit bottle of one Jaycy Lynz that Abigail asked them to find, then come to Carcosa proper. Through the war-torn city they go, arriving at a masquarade ball, where they deliver the bottle to Jaycy, enabling him to write the play that will cause all of this and thus fulfilling their part of the play. Their final fate depends on their corruption – how much their thinking has been warped by Carcosa, how close they are to it.

The madness of Carcosa

The core premise of the campaign is that everything and everyone touched by the King in Yellow is not only corrupted, but spreads this corruption further, all in service of the play. Delta Green’s STATIC protocol, mandating the extermination of anyone remotely connected to the play, is not only justified and correct but also hopelessly insufficient.

For player characters, this is reflected by a hidden attribute, their Corruption. It’s so hidden, the players are not supposed to know they have it. In many ways, it functions like a secondary Sanity attribute: it’s a horror game, everyone knows not to read cursed tomes (and reads them anyway). Read the play, and you’ll both lose Sanity and gain Corruption. However, Corruption also often grows when characters’ thinking simply aligns with that of Carcosa. Point out a name is an anagram from the play, be rewarded with a point of Corruption.

The higher their Corruption, the more they will see, understand, and even control in the Night World. But also, the more the forces of the King will single them out, and the more likely a bad end as they’re judged at the masquarade.

Madness in Carcosa

Sanity gets drained bit by bit throughout the campaign as the agents experience a myriad of impossible coincidences, doors that lead to wrong places, etc. There’s probably no other way to handle it in long-form play if you want to have a chance of a character surviving from the start till the very end. However, both me and my players ended up disliking the way it worked.

The players outright rebelled against the idea that their characters would keep being shocked at reality warping while they weren’t looking (or even when they were looking) in Night World. They felt that, after the first expedition into the Night Floors, they knew what to expect. The door they just walked through is now painted onto the wall? Just another day at the (night) office. One could argue that expecting corridors and rooms to appear and disappear at whim is not exactly sane behaviour, and the rules do explicitly forbid adapting to unnatural events, but you don’t really want to hear groans when asking for a sanity check.

As for me, any time such micro scare came up and the book suggested the agents could lose 1, or even 1d4 sanity, going through all the steps felt like a chore. That’s partially due to the DG ruleset, as not only do you roll to see if a character loses sanity, they then get an option to resist 1d4 of it by spending that much willpower (which we never ran out of, so this part was just an exercise in adjusting numbers) and reducing a bond by the same amount. In theory, that represents agents projecting trauma onto their loved ones, gradually alienating them all. In practice, bonds become unreachable and thus irrelevant by chapter 3, and the entire process was a couple of minutes of distraction any time something spooky happened, draining all tension from the scene.

Death in Carcosa

Every now and then, it felt like, the adventure remembers it is not only surreal horror but also a Delta Green campaign, and so should have a body count. The agents could be doing just fine, facing reasonable dangers and challenges, then BAM, deathly peril. This happens a number of times throughout the campaign. What’s worse (to me), is these moments are rarely telegraphed or even offer a chance to do anything but roll dice to overcome them.

The mall ambush, when DG may try to eliminate the agents it considered corrupted, can perhaps be seen coming, and can be approached in a dozen different ways. The mechanical lion in the apartment of Dr. Barbas can be avoided. But then the clown at the end of chapter 2 is just a roll-off with death. So is the conclusion of chapter 3, the race against STATIC. In the run up to chapter 4, in hotel Broadalbin, the agents stumble upon a thing that sends them into some kind of parallel reality, and they have to succeed on one of three sanity rolls to get out, with a huge penalty if they don’t reject it outright or fail the first one. Chapter 4 has several opportunities to die during, most likely, the final session of the campaign, including having to run across open courtyard under machinegun fire.

In a lot of these cases, the scare is greater than the actual danger. That hardly helps when dice do decide to kill you.

Despite what you might think, I’m not opposed to character death in principle. I do find it odd when a campaign where “look, see, the thing you last saw 20 years ago was just inexplicably created here before your eyes, don’t you feel trapped by the unseen forces of the King” is one of the major sources of horror, starts killing characters off for no reason other than to show it’s a DG campaign. The replacement agent is not going to have a visceral reaction to half of these revelations – that’s not theoretical, that’s how it played out for us.

Moreover, most of these deadly threats don’t feel earned. Not just because there’re sudden and unavoidable, but also because there’s no choice in facing them. The agents are in danger not because they’re trying to be brave or poking where they shouldn’t. They’re in danger because now there’s a clown chasing them and if it catches them they die.

Life in Carcosa

The Night World functions by a few very simple rules. If you want to achieve anything or go anywhere in the Night World, you have to a) fail a sanity roll; b) have high enough Corruption; and c) be at the appropriate part of the campaign/be allowed by the King. If you don’t satisfy these conditions, you’re going to have a bad time, likely reducing your Sanity and thus gradually improving your odds.

These rules are so simple, in fact, that my players kept overthinking it, coming up with much more involved and interesting explanations – partially because they didn’t know about Corruption. As one of the agents ended up with higher Corruption than the rest, he was more succesful at navigating the Night World while doing exactly the same things as his less Corrupt colleagues, and with more events targeting him directly, the party felt I was treating him as the main character.

The simplicity of these hidden rules, in turn, means that time and again the only meaningful thing the agents can do is to keep going forward. Everything that happens on the way is a distraction or an obstacle. Actually engaging with the scene is typically unnecessary, and often outright harmful.

Which is a shame, because by themselves these random encounters are good, creepy and strange. There are a whole lot of them offered in the Night Floors, and then some more in the Bookshop. But then at several more points in the adventure we’re told to use those encounters or come up with our own, so it would have been better if they had a separate dedicated chapter. And since the adventure relies on them so much, by the end the players realise they’re better off sprinting through – chapter 4 was a breeze for us.

This reaches its apogee in the Whisper Labyrinth near the end of the campaign. Not only do the agents have to phrase their “we go forward” action in a particular way, they have to get extra lucky even if they do. They also have no way of learning if they’re doing it wrong, or just need to roll better. And every time they don’t get extra lucky, they have a chance to have a (meaningless, draining) encounter. The place is meant to be a maddening slog unfortunate souls get stuck in, but actually running it that way just isn’t fun.

The actual story

The world exists to create the play that creates the world that will create the play.

IL is a very strange campaign. It’s full of great stuff. There’s almost too much: there’s no chance the players will see all of it, whole chapters of the book they simply won’t bother to uncover. It presents itself as an intricate puzzle. Any tiny bit of information can lead down a massive rabbit hole, and that rabbit hole will only leave you with more disparate pieces of info that may only become relevant in a future chapter. Some names, events, places, even faces, keep coming up. The players must feel like they’re trapped in a sprawling conspiracy.

They’re not. Here’s what’s actually happening: a dozen or so people, infected by the madness of Carcosa, are running around the atemporal backstage of reality, spreading the play. There’s no cause and effect, because linear passage of time doesn’t affect them. They don’t have a goal they could articulate either, they’re all too affected to have one.

For example, the agents could learn the Red Book edition of The King in Yellow play that damned Abigail Wright in 1995 and started their entire adventure is produced by Dr. Elias Barbas in the year 2015. He prints them and shoves them into the (atemporal, omnipresent, Pratchett-esque) Bookshop. That’s an “aha” moment, a piece of the puzzle sliding into place. But… so what? There’s nothing that they can do with this revelation.

Speaking of revelations, and this one is more subjective, but it didn’t feel like there was enough escalation in the campaign. For all the richness of the text, it feels like the main plot of the entire campaign is just repeating the Night Floors, louder and louder. Somewhere in the middle of the first chapter, my players came upon a marionette room in the Night Floors. Dozens of human-sized dolls, moving around in complex patterns, dressed like the agents and people they know. “Oh,” said one of the players, “That’s us, isn’t it. We’ve always been this.” And that was that, the entirety of the campaign, its mind-shattering revelation. The remaining campaign of 20 or so sessions was just going through the motions.

Our role in the story

The first chapter ends once the players decide to give up their search for Abigail. They probably do something with the Macallister building and its tenants, but that doesn’t affect much. The second chapter, for all its sprawling sandbox, ends with a predetermined scripted sequence that is entirely independent of what you’ve done to get there. So does the third one, except there the agents don’t even have to try and achieve anything, they’ll get herded into the last chapter when the GM decides its time. And the final chapter is about getting to the masquarade where the characters’ fate is entirely out of their hands.

Helplessness is a big part of horror. In a game where mere mortals come up against a reality-bending god-like force, it makes sense they wouldn’t be able to do much about it. It’s common for such adventures to focus on thwarting the equally mortal adepts of the eldritch gods, on delaying the inevitable apocalypse by another year.

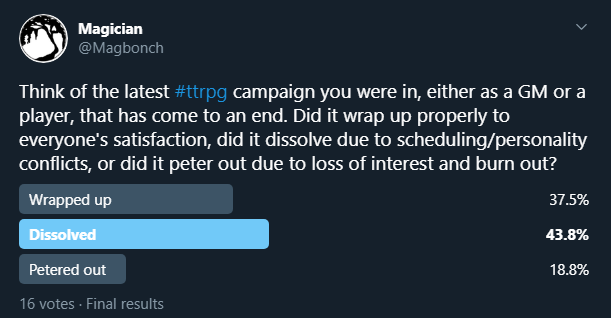

In IL, the mortal adepts are actually immortal, the poisonous play can be dropped off from the future, and the entire world is marionettes on a stage anyway. At no point during this adventure can the PCs change the outcome. They only thing they can achieve is surviving to see the end. This quote from the campaign author’s twitter offers some insight:

If you think every Delta Green op should be resolvable by Agents, you should reread it. Most of the time, the Agents have no idea what they’re facing or whether they defeated it or not. In the end, it is a game about futility. In other words, what it means to be human.

Many people, it seems, are drawn to the game, but fail to grasp that this futility is not a problem to correct. It’s the game’s CORE. Play as you like, of course, but without this essential ingredient of ambiguity and lack of “victory” it’s something else, not Delta Green.

Impossible Landscapes takes the ultimate futility of human existence in the face of (pre-)cosmic horror of the King in Yellow and multiplies it by the fact that the play is already written and all anyone can do is take their part in it. In other words, it’s a very fancy rollercoaster of a railroad, and you’re welcome to contemplate your insignificance while you ride it.

The secret stories

While I ended up disappointed with the overall structure of the campaign, I still love its tangents and side-stories, the actual things the agents investigate and uncover along the way. They are well-written, imaginative, and unsettling.

It’s a shame many of these plotlines are almost impossible for the players to discover. The demon summoning ritual stands out here. By the start of chapter 3 at the latest, the agents get a functional copy of Hygromanteia (itself a precursor to Ars Goetia), a demon summoning book. There’s an appendix providing a description for each of the 72 demons that could be summoned, and what their powers are. It’s cool.

Too bad that as written, the summoning ritual is almost impossible to achieve: after an hour-long ritual, the caster must make a reverse-sanity roll, with a -20 penalty for every other character present (nothing in the text hints having others present is a bad idea). Meaning that at best it’s a coinflip if anything happens, and if the entire party is involved it’s all but guaranteed to fail. Failure means the caster can never successfully perform the ritual. Success means you’ll get a response within a day.

So a party would try it once or twice, get no response, and conclude the ritual is a dud. At the point in the campaign they’re likely to gain access to it, they no longer have the luxury of messing about. It is, I’ll grant, a properly arcane ritual. But it’s meant to be a power the party gains, not an obscure easter egg (which takes up 13 pages of the book).

It’s even more of a shame that even seemingly important (and interesting!) plot lines lack meaningful resolution. Maybe it’s written that way to hint at the larger, unknowable picture, but as a GM I’d rather have the answers and watch the players fail to grasp at them, than feel like I’m not getting it myself and thus can only offer vague hints to the players.

The most egregious example of this is the patzu. It is introduced in chapter 2 as a big deal: patzu is condensed Corruption that can be extracted from individuals exposed to the play, it is what the King consumes, the entire point of the play and the world. Drinking it takes one back to the “real” world, which is instrumental in escaping the chapter.

Reading that part of the campaign I felt like this was it, we were getting somewhere, with this information the agents would gain some measure of agency in the campaign. And then we barely hear about it again. It’s not a major new tool in the agents’ arsenal, nor a part of a larger scheme to uncover, nothing. It might be a component in the creation of the spirit bottles which contain the answer to a person’s innermost question, but that connection is unclear, and not actionable.

Patzu is, apparently, a part of the DG/CoC mythos, originally mentioned in the Sense of the Slight-of-Hand Man campaign for CoC, also written by Detwiller. Which is meaningless within the context of IL, but revealing of a larger, perhaps more inisidious truth.

But before we get to it, another example: the inciting incident, the disappearance of Abigail Wright. We’re told she has moved in with an “encyclopedia salesman”, whose identity is strangely obscured, and not just from the players. We know virtually nothing about him, only a brief description of what he looks like if the agents catch a glimpse (but they can never chase him down), not even a name. And that’s in a book that goes on page-long detailed backstory tangents full of information players would never uncover for every other NPC they meet. Was this a hint at the King or the Author in the original adventure? It’s probably not anymore, just a dropped tangent, because the Author is definitively named as Jaycy Linz.

Who is Jaycy Linz? A character from a short story by John Tynes, itself a part of King in Yellow “mythos”. Why is he here? Why did Abigail ask us to fetch his spirit bottle to make him the Author? As a reference. Realising this actually made me a bit angry. This was the easiest, most obvious way to tie the entire Abigail sub-plot together, to have the would-be Author be the salesman from the Night Floors, explaining her role in the story. Offering one of the agents a chance to always have been the Author would have worked, too. Instead, we get a reference to an out-of-print book or a webarchive page.

How many other characters and places in this campaign are references, not just to the original stories but the expanded body of work? My guess is a lot of them. The ones who are not are references to the demons of Ars Goetia instead. Does it matter if something is a reference if you don’t recognize it? Maybe not, but what if the “supplemental material” helps make sense of some of these characters and plot lines? And why does a 363 page campaign book need supplemental material?

The roleplaying hobby is full of references to fanfics to homages to reimaginings, that’s the entirety of D&D and Call of Cthulhu (and by extension Delta Green). But the reference itself should not be the point. Impossible Landscapes, I feel, sometimes forgets this.

Reimagining the story

The campaign is so vast and detailed, you can only fully examine it in hindsight. Now that it has been played all the way through, the curtain has fallen only to rise again. Despite all my criticisms, I don’t regret running it. So what have I learned, what should I have done differently – and maybe you’d wish to consider?

While reading the book, some parts of it immediately stood out as troublesome: abrupt opportunities for character death, keep-rolling-till-you-get-it sections. I set the doubts aside, the campaign gets rave reviews, maybe I just don’t get it and should embrace the artistic vision of the author. “Plus,” a tiny voice in the back of my head said, “how can you write a review if you change it too much?”

None of the things I’ve outlined may cause any issues for you, but I knew they would for me, and plunged head on into them anyway. Lesson learned: I have enough experience to know what will and will not work for me and my group, and should rely on that experience over any adventure’s authority. So sanding off these rough edges to taste would be a start.

I’d also ease up on alternate realities, though that might be tricky to do. The entire point of chapter 3 is to drive home that there’s no “real” world, but I’m pretty sure my players concluded they were simply wandering around warped splinter realities since leaving chapter 2, with the real actual world safely behind all the madness.

A bigger change would be to adjust the entire premise of the campaign. Instead of the inevitability of the play being guaranteed by the atemporal backstage shenanigans, I would try and represent it as malignant destiny, arising incidentally but no less inevitably from the actions of those infected by the play.

Which would in turn mean the key NPCs actually need something to strive for. As is, they’re all stuck and insane. Many want to find their spirit bottle, but they’re not even doing that – they have a role in producing the play, after all. Even the demons Bael and Guison (Mr Wilde), who seem to be actively doing something, don’t actually have an objective, or even an implication of one. My players were certain the demons were another faction in the cosmic conflict – so let them be. Carcosa is perpetually beseiged by an unknown force, the Black Wind army – let it be the demonic army, with King Bael trying to take over the role of the King.

For that matter, and this is something I’ve actually done, replace the final judgement at the masquarade with the award of masks for the next performance. The masquarade is the afterparty, and once you make it there and take off the mask you didn’t know you wore, you learn that’s what it’s all about: who gets to play which part when the world is recreated to recreate the play. And of course one of those attending doesn’t wear a mask…

An even bigger change would be to ditch the campaign’s structure. Turn the game into an actual sandbox: the agents are caught in the periphery of the play, but they don’t have a role in it unless they take one up. Keep the actual content of the book, but don’t mandate the chapters and transitions between them. Instead, let the agents use the Night World to go to any other place and time touched by the King that they’re aware of. Macallister building, Dorchester house, the Bookshop, Broadalbin, etc. – all are fair game. Expand the list to include Chateau Castaigne in the 15th century, some place in Paris in 1895 when the play was first performed, and so on, let players explore the tangents they want to pursue.

Time travel is an issue, of course. The STATIC killer(s) would be repurposed from guarding the approaches to Carcosa (they aren’t very good at it anyway – everyone who’s anyone just wanders into Broadalbin through the Night Floors) to hunting down agents trying to change history, stay in the past, etc.. Plus the malignant destiny of Carcosa gets to play a part: change one thing, and watch it be the cause of the outcome you tried to prevent.

No mater which path they take, the agents would eventually find their way to Carcosa, arriving just in time, always, for the masquarade at the end of the world.