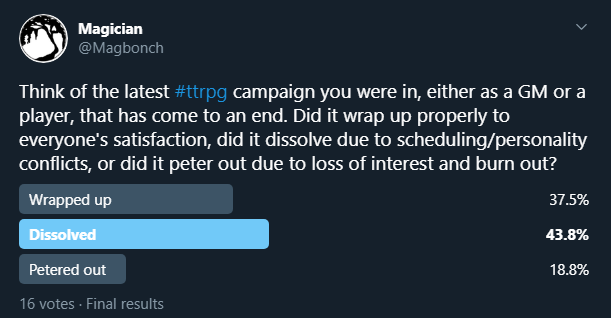

Roleplaying campaigns end all the time. Too bad they rarely finish. It took me years of GMing to actually complete a campaign, not merely see it dissolve. And I’m not the only one:

Far from a representative poll, certainly, but it lines up with my experience. Almost 2/3rds of campaigns don’t reach a satisfying ending. Why do campaigns fail, and how can we improve our chances?

A roleplaying campaign, traditionally, is a sequence of games with same players controlling same characters, with some sort of overarching plot. Anything that goes beyond a one-shot, basically. Finishing a campaign, therefore, typically means resolving this plotline (save the kingdom), personal plot threads PCs might have created or started with (avenge parents’ murder), as well as the majority of plot threads that came up along the way (whatever will happen to the goblin gardener the party had befriended against all odds and seems to care about much more than saving the kingdom or discovering the parents’ murderer).

There’s a plethora of ways to play roleplaying games, none of them wrong. It’s certainly possible to have a sequence of sessions with the same characters going on adventures that don’t have an overarching plot outside the adventures themselves. Perhaps you’re just playing through published adventures one after another, or running a hexcrawl. In that context, finishing a campaign could be as easy as deciding the characters have retired and opened a tavern together – or, more likely, have all perished due to a sereis of bad rolls and worse decisions.

I’m currently running such a campagin as a backup. However, most of the games I’ve ever run have been more, for lack of a better word, ambitious, even when I could not possibly fulfill these ambitions. Like many others, I began my GMing “career” with D&D. It took me a bit to be comfortable enough with the rules to make up my own adventures, but it turned out that campaigns were harder. A large part of that are basic storytelling skills, which take time and effort to develop along with other GMing skills and system mastery.

I often had the start and the end in mind, but no idea how to get from A to Z. And it was always “Z”, not “B” or “C” – a distant, pie-in-the-sky goal. Before we’d get anywhere near an ending, the campaign would fall apart. Ancient prophecies would go on unfulfilled, worlds unsaved, great wrongs unavenged, evil gods unslain. I kept imagining awesome, epic events, and never actually playing through them. I don’t think those were bad games, but they weren’t going anywhere, and I suspect it made it easier for everyone, myself included, to give up on them. It took playing in another GM’s game that actually wrapped up nicely for something to click. I ran a complete campaign that resolved to everyone’s satisfaction soon after. It wasn’t D&D, and it wasn’t a many-year epic, either.

That game was Dark Heresy, and we played through the entire campaign in about 6 months. Why does it matter? Well. I believe the basic structure of character advancement in D&D inadvertently sets its GMs up for failure, and breaking away from its paradigm helped me run a campaign with an actual ending. Paradoxically enough, after a few of these shorter finishable and finished campaigns, I was actually able to run a complete D&D 4e campaign that went all the way from 1 to 30 over 3 years, and had served as the basis for this blog for quite a while.

What’s the first thing you learn about D&D characters? They start at level 1 and go to level 20. First you fight goblins and skeletons, then demons and beholders, then dragons and… larger demons, I guess. You top it all off with a fight against some evil deity or maybe the tarrasque or some other world-ending monstrosity. That’s the implied campaign structure right there.

At a reasonable pace of 5 sessions per level up, that puts us at 100 sessions, or 2 years of weekly games. From purely pratcical point of view, that’s a huge commitment. And then there’s burn out and maintaining a semblance of a coherent narrative throughout. Still, over and over, I’d take aim at a grand finale, seed hints and prophecies, all the while throwing giant rats at the 1st level party.

Now, D&D doesn’t say you’re supposed to only play 1-20 campaigns. It just scatters the character progression charts and all the cool monsters, spells, and magic items before you, a field of very shiny rakes to step on. One solution would be to figure out the level range in which you want to set your game – the actual game, not the goblin-hunting build-up, unless that’s what the game’s about – and play there. Of course, that runs into the other issue: D&D is Not Very Good at high level play. It just gets more and more complicated and unwieldy, and the only way to mitigate that is system mastery by both GM and players. Which, in turn, requires lots of experience. But any group starting a campaign is likely to have players who’re new to the system or roleplaying games in general. So you start at level 1, and by the time the players are comfortable with their characters and the rules, the campaign has fallen apart. Catch-20, if you will.

I’m so fond of this joke, here it is restated in a punchier way:

D&D is complex at high levels, meaning one has to start at low levels and gradually increase system mastery of the entire party. But campaigns often end before you go all the way from 1 to 20, so you never get to play at high levels. That’s Catch-20.

Maybe you do want to start at level 1, to watch the characters grow from nobodies into mighty heroes, to bond with their fellow adventurers over a campfire, a found family that slays together and stays together. Some D&D spin-offs, such as 13th Age and Shadow of the Demon Lord, condense the levelling experience to only 10 levels, much more manageable. They also both suggest a campaign mode where players level up after every session. Back in my D&D days I rejected such ideas as “unearned”, whatever that meant, but the whole point of this article is to help you avoid my mistakes.

And then, of course, there are entirely un-D&D-like systems without character progression charts or implied campaign arcs to hold you hostage. Many, like Fate, Apocalypse World or Spire (and a whole host of others, I don’t mean to imply this is a modern phenomenon) are open-ended: you can keep earning advancements for your character for as long as you play. By removing the prescribed order in which you gain abilities these games also removed the unspoken campaign structure. The campaign doesn’t get needlessly stretched out to fit the implied arc. I’m particularly fond of the approach Heart took, a Spire spin-off I’m yet to play properly. In it, the most powerful abilities characters can get also end them, one way or another. An entirely different kind of implied campaign arc.

So, what are the actual practical take-aways here? I’m glad I asked. First and foremost: don’t start a lengthy campaign with people you’ve just met. Looking back to the poll for the reason campaigns end prematurely, group dissolution is far ahead. This is largely outside of GM’s control. Players may not get along with one another. They may want different things out of RPGs. Their priorities may shift, or life circumstances may change. Most of these are exacerbated by inviting new people you’ve never played with before. Which is not at all to say you shouldn’t do so, how else would you build a gaming group. Still, some or all of these players may drop out sooner or later. Since this is something you can’t control, you have to take it into account. So, when faced with building a new group, come up with a campaign that take weeks or months, not years to resolve. Use this as an excuse to try different games, there are so many good ones out there.

For that matter start with shorter campaigns yourself before you attempt something massive. Grow those storytelling and GMing skills. A few finished short stories are much better than half of a fantasy epic that gets abandoned – take it from someone with half a novel languishing out there on the Internet.

It’s hard to give generic advice given how many different kinds of campaigns and playstyles there are, but here are a few ideas. Figure out a manageable end and major steps on the way there, then hit them relentlessly. This doesn’t mean you should have a prescribed ending you steer your group towards. A common approach is figuring out what would happen if PCs do nothing, then seeing where they take the situation. The key here is maintaining momentum. Even if there is no “global” plot, there likely are individual stories PCs bring to the table.

If you do want to run a lengthy campaign, structure it like a tv series made up of several seasons, each its own arc and a satisfying hopping off point. They don’t know if they’ll be picked up for the next season, and neither do you.

And finally, and this is something I’ve constantly struggled with, use cool ideas as soon as you can, don’t hold them back for the climax that may never come. You will have more cool ideas later, you’re a GM, that’s what you do. But unless you bring your ideas to life at the table, all you’re doing is daydreaming.